Brodie’s bone studies

Salisbury Infirmary apprentice?

Sir Benjamin Brodie (1783-1862) was one of the most distinguished surgeons of the 19th century and became the first Serjeant-Surgeon to Queen Victoria. He was primarily associated with St. George’s Hospital in London.

A label for a portrait in our archives states he was apprentice at Salisbury Infirmary but no records or evidence have been found, so far, to corroborate this statement. The print dates from 1821 which is only 20 years after Brodie left to go to London, so if it was purchased at this time it is possible that these details are correct, as they are well within recent living memory. However the label must date after 1834 when Brodie was made baronet and took the title of ‘Sir’

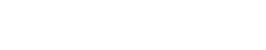

Brodie was born in Winterslow, a village 7 miles east of Salisbury. His father was a local clergyman and we can see from the financial records of Salisbury Infirmary that the Rev. Brodie was a charitable subscriber from the hospital’s outset, giving annually £2 2s (2 Guineas) in 1767, this increased to £5 5s annually up until his death in 1804. Later records show Brodie’s brother, Charles George Brodie Salisbury Banker, was a House Visitor to the Infirmary. (An official role given to persons paying a subscription of a certain sum and were required to visit the wards weekly and “inspect” carrying a white wand, accompanied by Matron and House Surgeon, with the patients standing by their beds. This was on a rota.)

Salisbury General Infirmary, founded in 1766, was a prominent regional hospital during Brodie’s time in Wiltshire. It is likely this brought him into early contact with the Salisbury medical community. It’s plausible he trained or visited the Infirmary in his youth or early career before moving to London at the age of 18.

While specific age requirements varied and changed over time, some 18th-century apprenticeships for surgeons or other trades could begin for very young individuals, even under the age of 12, according to one study on London apprenticeships.

Apprenticeships were sometimes formal, involving signed documents, but could also be informal, with young men living and working under the mentorship of a family member or established practitioner. Apprenticeships focused on learning by doing and watching. A surgeon’s apprentice would observe and assist their master, gradually taking on more complex tasks. Unlike today, there were no formal medical schools in the modern sense at the start of the 18th century, and training was primarily through apprenticeship.

Joint diseases described

Brodie’s surgical techniques and writings likely influenced physicians at Salisbury General Infirmary, even if he didn’t work there directly. He wrote influential texts like Pathological and Surgical Observations on Diseases of the Joints (1818) which were widely read.

This work revolutionised the understanding and treatment of joint disorders in the early 19th century. Moving beyond vague diagnoses like “white swelling,” Brodie classified joint diseases into distinct types, emphasising accurate diagnosis and often advocating conservative management over amputation. Drawing on meticulous clinical observation and detailed pathological study, he described conditions now recognised as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and tuberculous arthritis. His humane, evidence-based approach influenced generations of surgeons and marked a turning point toward modern orthopaedics.

Education

Sir Benjamin Brodie made lasting contributions to both clinical medicine and medical education through careful observation, innovative testing, and reform.

In 1846 he described the physiological basis of what is now called the Brodie–Trendelenburg test, a method for detecting faulty valves in the veins of the leg. By elevating a patient’s limb to empty the veins and then applying compression before standing, he demonstrated how to pinpoint the source of varicose veins, a technique still incorporated into modern vascular examinations.

Earlier, in 1832, Brodie documented a form of chronic, localized bone infection that now bears his name: Brodie’s abscess. This subacute osteomyelitis, often affecting the tibia, presents with slow-onset pain and minimal systemic symptoms and is still treated with surgical curettage and antibiotics.

His keen diagnostic sense extended to joint disorders. The term Brodie’s knee, first used in 1813, covered both true inflammatory or tuberculous stiff-knee disease and cases where the joint appeared frozen without structural damage, a forerunner of today’s understanding of functional limb syndromes.

Brodie was also ahead of his time in recognizing systemic patterns of disease. In 1818 he described cases of reactive arthritis, linking urethritis, arthritis of the lower limbs, and eye inflammation. Later, in 1850, he offered one of the earliest clinical descriptions of ankylosing spondylitis (then unknown by name), noting progressive spinal pain, stiffness, and eventual vertebral fusion; “The progress of the disease was tedious, extending, when I had the opportunity of watching it, over a period of several years, and it terminated in leaving the spine of its natural figure, but completely rigid and inflexible through the greater part of its extent.”

His treatments reflected the era, using mercury, iodides and sarsaparilla.

Beyond his clinical insights, Brodie reshaped British surgery. He established the Fellowship examination of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1843, raising professional standards, promoting humane patient care, and supporting the education of women physicians. His mentorship of figures such as Florence Nightingale and advocacy for pioneers like Elizabeth Blackwell underscore a career that combined medical discovery with a commitment to reform and education.

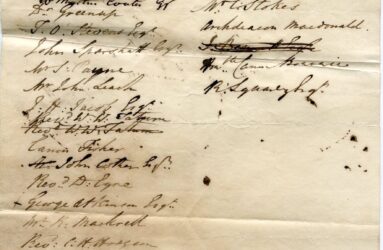

In 1858, the famous book Gray’s Anatomy was dedicated to Sir Benjamin Collins Brodie. This book is still used today to teach about the human body.

About the printing technique

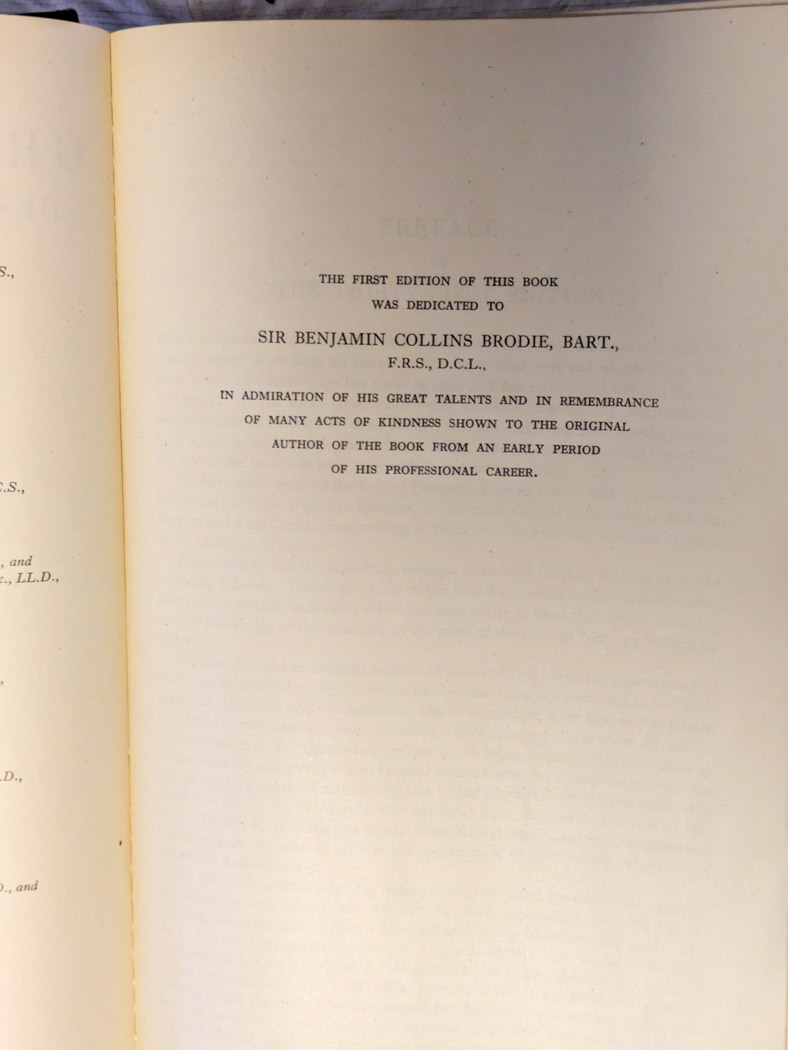

The engraver was Charles Turner who specialised in portraiture. In his career he also collaborated with J. M. W. Turner who he was not related to. This picture is a mezzotint reproduction of a portrait painted by artist John James Hall in 1821.

Mezzotint is a printmaking technique that produces rich half-tones (greys) by roughening a metal plate to hold ink, allowing for subtle gradations from deep blacks to delicate highlights.

Mezzotints were made of historic paintings because the technique’s ability to render deep shadows and smooth tonal gradations made it especially effective for reproducing the dramatic light and atmosphere of oil paintings, allowing wider audiences to experience and collect images of famous artworks in an age before photography.

Portrait style and features

The portrait of Brodie is a three-quarter seated view which is common in formal portraiture, it gives a dignified presence without being overly confrontational. His head turned slightly toward the viewer and conveys alertness and engagement, as if he’s about to speak.

One hand holding an open book; this emphasizes intellectual and scholarly qualities, an important symbol for a man of science in a pre-photography age.

He wears a double-breasted dark coat with high collar which was fashionably formal in the early 1800s, signalling a professional gentleman of high standing. His white cravat and waistcoat are markers of refinement, wealth and propriety; the crispness suggests meticulous self-presentation, echoing a surgeon’s precision.

Interestingly there is an absence of surgical instruments which is deliberate; medicine was still striving to be recognized as a learned profession, so book and intellect were more prestigious symbols than tools of trade.

In portraiture of scientists, doctors and intellectuals of the time, books stood in for learning with a career rooted in study, not just manual skill. It also conveys authority, knowledge and professionalism. It can also mean moral seriousness; unlike portraits of aristocrats with dogs or hunting gear, a book framed the sitter as contributing to public good.

The engraving is working to place Brodie firmly in the tradition of the learned gentleman-physician and as a man whose authority rests on a combination of study, intellect and moral responsibility, not just practical skill.

It would have been instantly legible to contemporaries as the image of a man you could trust to make life-and-death decisions.

See resources How to read a portrait