Cider in the snow

In Easter 1966, Maureen, then a student training to be a teacher in Kent, volunteered for the Medical Research Council’s Common Cold Unit near Salisbury. She hadn’t initially planned to go alone, her friend Pat had persuaded her to sign up; but when Pat caught a cold just before departure, Maureen decided to continue on her own. Living in Essex at the time, she was reimbursed for her train fare and remembers arriving at Salisbury station, where a minibus collected her and other volunteers for the journey to the research site.

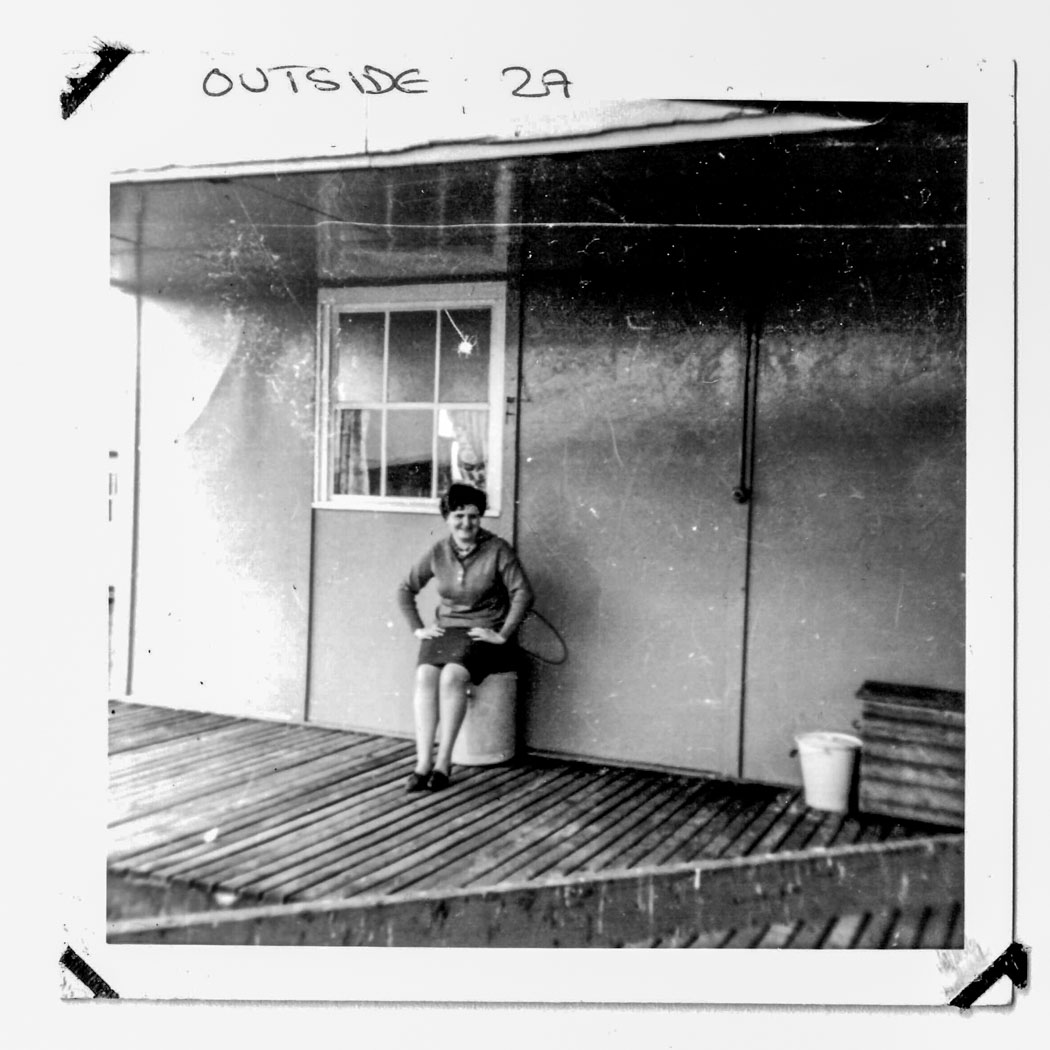

The setting left a vivid impression: rows of Nissen huts connected by wooden walkways, isolated in the Wiltshire countryside. Maureen was placed in a hut with another student, Susan, who she had not met before but got along with well. Their accommodation had three small bedrooms, a lounge, kitchen, bathroom and a medical room, all within the same converted hut. Though designed for three people, only the two of them occupied it after Pat’s cancellation.

The experiment was carefully controlled. Each morning at about nine o’clock, a doctor and nurse visited to collect throat and nasal swabs, check symptoms and deliver vitamin tablets and nasal drops, one of which might have contained the cold virus.

Maureen recalls filling in daily health reports and being asked whether she had developed a sore throat or any cold symptoms. In her case, she never did.

Life inside the unit was both regimented and oddly domestic. Meals were delivered twice daily in large metal containers, placed in wooden boxes outside the huts. Volunteers had to wait until the staff member had moved 30 feet away before collecting their food, maintaining strict isolation. Breakfast was self-catered, but everything else was provided, and the food, Maureen remembered, was plentiful – sometimes even including cream cakes. The volunteers could telephone the admin office to request library books, jigsaws, or supplies like milk and bread. There was no television, only a radio, so time was filled with studying, jigsaw puzzles and board games.

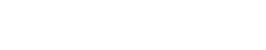

Outdoor exercise was encouraged, provided they stayed 30 feet from others. Maureen and Susan went for walks in the nearby countryside. She remembers one outing to Homington village where they had to make a wide detour to avoid a passerby walking a dog. During the stay, light snow fell, and in a touch of student ingenuity, they used it to chill their cider bottles beneath the hut. Volunteers were also given a daily allowance of seven shillings and sixpence, along with their choice of a daily bottle of beer, cider, or squash. Maureen says it was quite generous for a student at the time!

After about ten days, the trial concluded. The participants were shown around the laboratories, given a meal together to share their experiences, and taken into Salisbury to visit the cathedral before heading home. Maureen never returned for another trial, though she recalls the experiment fondly as a unique experience.

In later years, when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, Maureen reflected on her time at the Common Cold Unit. She even wrote a short article for her local U3A newsletter, noting the parallels between her 1960s isolation and modern quarantine life. She was surprised to learn that the coronavirus family was first identified at the Cold Unit during the very era she had volunteered, news that had not been widely known at the time.

Now living in Salisbury, Maureen looks back on her time at the Cold Unit with amusement and pride. Though she thought it closed without producing major scientific breakthroughs, she sees her participation as a small, intriguing footnote in the long story of medical research and perhaps, by fate, one that quietly drew her back to the city where she once volunteered as a student.

Listen to Maureen talk about her time as a volunteer: