Odstock’s beginnings as an American Field Hospital

Summer 1942

Ted Trowbridge, a local man from Bowerchalke, worked as a bricklayer on the Odstock site as part of a team of men from the building trade under an Essential Works Order. He was paid 1 shilling and 9 pence per hour. His main task was to build brick footings for nissen huts to be used as wards. There was no sanitation inside the huts – mobile patients used ablution blocks nearby and electricity was supplied for lighting only. Potbelly stoves were built into each ward to provide heating. Source: Richard Bolton

The 5th General hospital relocates

On 12 December 1942, the 5th General Hospital transferred their hospital structures, together with the 361 remaining patients to a new location near Salisbury. On 8 December, an advance party of 5 Officers and 43 enlisted men had travelled in 18 vehicles from Northern Ireland to Odstock and prepared for the reception of the main body, which were expected to arrive ten days later. It was impossible at this time to secure rail and/or water transportation for the main body so arrangements were therefore made for air transportation.

Except for the advance group, the motor convoy and the rear guard party with its personnel of 4 Officers and 42 trucks with heavy baggage and equipment, all personnel were moved by air requiring several trips. 31 Officers, 66 Nurses, 268 Enlisted Men, 11 female civilian employees and assigned Red Cross personnel were transported by air without incident, including 50,000 pounds of personal luggage, medical equipment and records.

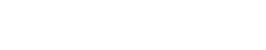

The building at Odstock was of the standard British brick and Nissen hut type. Originally planned for 600 beds, it was expanded to a 1,000-bed capacity. There were twelve standard brick construction wards with a normal capacity of 32 patients each; in addition, there were two large Officers’ wards, one isolation ward, and six other wards.

Space for the operating suites was adequate, as it was for the X-Ray, Linen, Pharmacy, Central Supply, Laboratories, Dental Service, Administration, Medical Supply and utilities.

Hospital buildings

The most urgent needs were repairs to a leaky roof. It was found that the facility had neither heat nor electricity. Living quarters and washing spaces were both impaired by water drainage. Installation of 110V current was also necessary before much of the American hospital equipment could be used. Hard surface roads and walkways had to be constructed in the newer Nissen areas to provide better means for fire protection, moving bed patients, delivery of coal and medical supplies and collection of waste.

Outside corridors between wards needed to be enclosed. Gas provision was needed for laboratory, pharmacy, central supply and dental building. Hospital personnel and American Engineer units increased the overextended British labour force at most construction sites. Medical personnel were also engaged in other activities, including roofing of outdoor walkways, pouring concrete foundations, painting, brick laying, and even installing of wiring and plumbing.

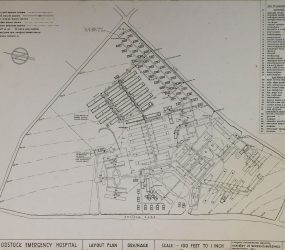

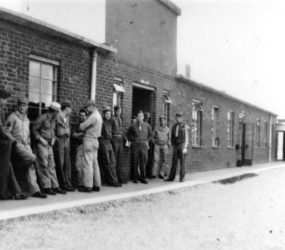

After completing the majority of the required repairs, modifications and adaptations, the 5th General Hospital formally opened on 1 March 1943, renamed as the 158th General Hospital. During this period the organisation cared for a total of 10,004 patients. In addition to its normal functions, the 5th General Hospital established special facilities for care of soldiers suffering from ‘combat fatigue’. The photos below show Odstock hospital during World War 2. Read about those who remember the hospital at this time.

D-Day Landings

On the 6 June 1944 thousands of Allied troops began landing on the beaches of Normandy in northern France at the start of a major offensive against the Germans. The invasion would be codenamed ‘Operation Overlord’.

US soldier Clinton Gardner, while recovering from surgery at a hospital in Salisbury, told his story of that fateful day. Gardner said: ‘We landed at 9am expecting that our troops would be a mile inland, and they were only 300 yards inland. So they in fact were fighting on the cliff, trying to get up the cliff from the beach. It was just beyond the surf; we were still on the sand. There were about 200 to 300 bodies lying in the water and the beach, just in his immediate area. There was even some who thought that we wouldn’t continue the invasion at that point.’

The invasion did continue with about 160,000 Allied troops landing on a 50-mile stretch of French coastline for the operation that would turn World War II in the Allies’ favour.

Around 5pm, shrapnel from a mortar that landed near Gardner pierced his helmet. He was carried to the base of the cliff, but it would be another 24 hours before he receive medical attention. Gardner said, ‘I didn’t think I would survive … I was able to put two hands in the hole in the helmet. A British captain representing London’s Imperial War Museum visited and asked for the helmet. The hole, the captain told Gardner, was the largest he had seen worn by any survivor of World War I or World War II.’

Gardner was a member of the highly decorated 110th anti-aircraft artillery battalion and he received the Purple Heart twice, for the injuries he sustained on D-Day, and later for injuries he sustained at the Battle of the Bulge six months after the invasion.

Source: http://www.unionleader.com/article/20130606/NEWS18/130609567/-1/news

Pictured below is the 50th anniversary commemoration of the D-Day landings and US Army medical services, that took place on the Green in 1994. Alongside it the World War 2, 48 star US flag that is in the hospital’s history collection.

Find out what happened to Odstock Hospital after the war?

Read more about Odstock hospital’s history and how it became Salisbury District Hospital.