A visit to Fisherton Asylum

What reasons do we have for taking an interest in historical artefacts? One reason could be the way it helps us hold up a mirror to our own views, beliefs and assumptions. Reading documents and accounts from another time shows up, in heightened detail, what has changed in society, what is the same and how attitudes shape a given period. Lately, we came across an article ‘A visit to a Convict Lunatic Asylum’ written by William Gilbert and published in Cornhill Magazine in 1864, which highlights this changing of attitudes in how we treat, discuss and regard mental health disorders.

From the outset the term ‘lunatic’ in the title of Gilbert’s article could be considered loaded and offensive by modern standards. It is an antiquated word to describe someone seen displaying madness, deranged or crazy, originally considered as a disorder caused by the moon ‘lunar’. Similarly the word ‘asylum’ has changed meaning, the now dated meaning conjures images of harsh mental institution, like ‘Bedlam’, and its connotation of chaos, from the name of the Bethlam London psychiatric Hospital. A more contemporary reading of the word would mean those seeking shelter, support, political asylum from tyranny and so on. The article is fascinating to us now as it describes, in fine detail, Gilbert’s visit with a medical friend to an inmates’ social ball at Fisherton Asylum, later known as Old Manor Hospital, Salisbury. Find out more about the history of the hospital site here.

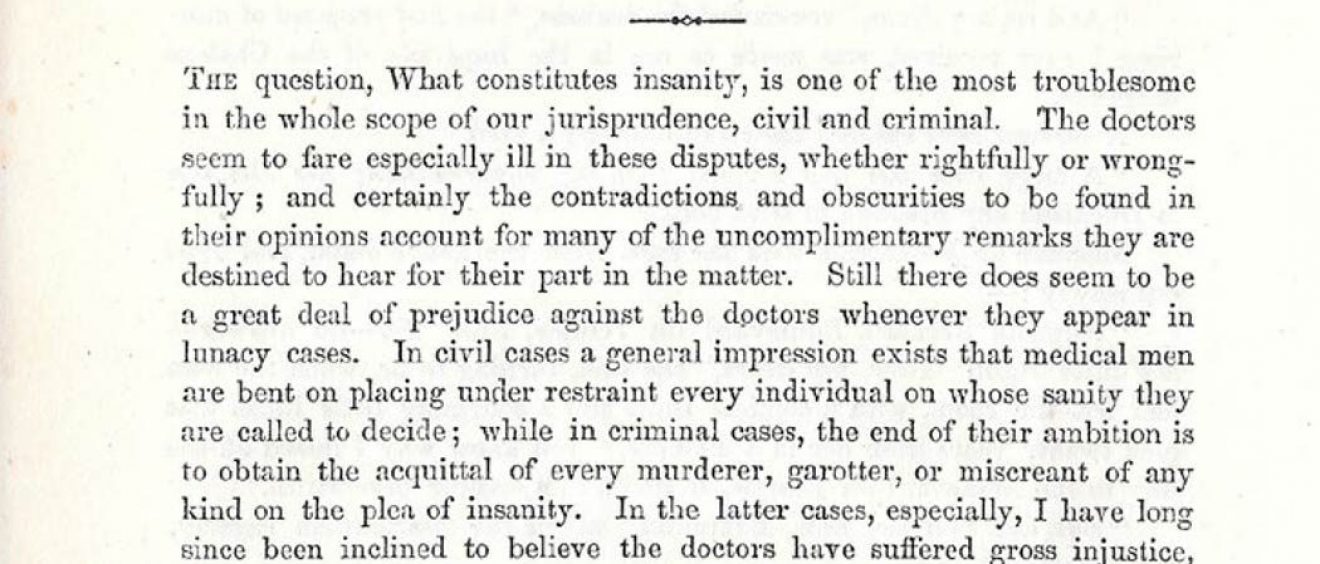

Gilbert was an Assistant Poor Law Commissioner and was interested in the treatment of criminal patients and with this article challenges preconceived ideas and assumptions, of the time, regarding medical diagnosis and patient behaviour. When invited to this patient social event he asks his colleague ‘But is it not a rather dangerous thing to allow a number of convict lunatics to assemble together?..’ ; To which his friend replied ‘… you will admit you never saw a more well behaved or orderly assembly in your life.’

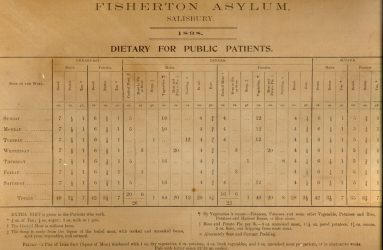

The wider hospital complex was described as ‘… like a village. It comprises many houses, separated by high walls, so that the patients may be divided according to their cases and accommodation they require; for there are others than convicts here …’ Their arrival at the Asylum ‘resembled a remarkably handsome villa … and the beautifully arranged grounds favoured the illusion’. Gilbert and friend were received in a ‘parlour’ by Dr Lush the principal. Passing through the grounds with him, Gilbert notes that apart from ‘every door was locked …there was nothing to mark it from any private gentleman’s house’. The doctor unlocked the door to a single-story building with high roof and they entered a ball room, 60 or 70 feet long, and lit by gas lamps. He describes the high ceiling and the ‘orchestra’ [separate area from the stage where musicians played] which ran the width of the building and 10 foot from the floor. The band were a dozen musicians dressed in uniform and a piano stood at the other end of the room. The entertainment for the evening comprised of dance and song.

The ball was attended by men who stood on one side and women who sat on the opposite side, they did not speak to each other. Gilbert noted some were dressed in fine society costume whilst others ‘appeared exceedingly poor’; whilst the women had made many paper flowers. The brass band played a quadrille followed by a mazurka and many joined each other to dance with ‘gravity‘ and ‘courtesy’. An old woman played piano to accompany song ‘Jock of Hazeldean’ [Scottish folk song about a woman who didn’t want to get married and eventually ran away]. When Gilbert asked one of the attendants more details about the group of patients he was told:

‘The majority are prisoners for various offences – burglars, thieves and murderers’. Gilbert replied, ‘Murderers! Are there any murderers here?’ ‘About thirty’ the attendant answered, quietly, and without anything like aversion in his tone or manner. Gilbert was directed towards ‘a slim man, in velveteen coat and trousers, with a very pretty girl for a partner. “he was formerly a celebrated burglar, who went mad on solitary confinement, and attempted to murder the prison doctor. The girl is here for murdering her sister”’

Gilbert, concerned with safety, was told that the band were all trained warders and several male and female warders were amongst them in the hall. At the end of the evening, Gilbert discusses the patients with Dr Lush who states, ‘You have tonight seen them on their best behaviour’. When Gilbert asks, ‘But is not a ball a singular amusement for such people?’, the doctor replies that they ‘… ought not to be treated as criminals. Dancing is the only amusement they enjoy.’ To which the doctor invites Gilbert to return the next day to find out more.

The following day the doctor shows him through the male convict area:

‘… although I have here under my charge some as unmitigated ruffians as the world holds, I have not a pair of handcuffs, or a lock-up cell, or any instrument of punishment whatever, in the whole establishment’.

Gilbert asks, ‘In what manner do you maintain order then?’

‘Principally by kindness’ and presence of numerous ‘powerful staff of warders’ who ‘even if they are struck, I do not allow them to return the blow’.

‘When I said I had no punishment, I should have state I have one. When a man misconducts himself, I do not allow him to attend the balls for some weeks’

The inmates’ rooms are described as well ventilated, light, clean and beds arranged in a row opposite the windows, whitewashed walls decorated with coloured prints depicting moral or historic subject matter. The windows were without bars, but had metal frames that would only open a small amount to allow air but not space to escape. However, in the centre was an iron cage around a bed, for the protection, of night-warder to sleep safely in the room.

Other scenes are the ‘handsome chapel’ and well-tended grounds. He described the gardener working with a team of inmates, who benefit from a few hours labour, less arduous than they would be used to, growing all the vegetables that were consumed in the hospital. And they are rewarded with a pipe and tobacco at the end of the work.

Gilbert spoke with a doctor who had murdered a young woman and a Polish Count who had ‘become mad in solitary confinement’ during punishment for swindling; and a young sergeant who killed his wife and children; and a man who thought it reasonable to kill a tax collector for an outstanding payment for keeping a dog; or the man who self admits during bouts of alcoholism.

Perhaps one of the most interesting scenes is the one that describes a woman, who had been punished in prison for her behaviour, ripping clothing, tearing up the floors ‘more a tigress than human being’ (a classic presentation of female hysteria). When admitted to Fisherton she appeared calm for some days but ‘at last got into one of her passions’, was held by the warders who ‘made her no threats, nor did they attempt to calm her, but quietly stood by her side looking at her, not only without anger, but with perfect indifference. She continued in her rage till she was utterly exhausted…’ She recovered not understanding why she wasn’t being punished like in prison. However, most thought-provoking, the doctor explains she remains a ‘most dangerous patient’ and her ‘attacks of passion were invariably preceded by a sulking fit of two or three hours …’ When staff noticed this behaviour treated her with ‘a simple medicine, excited a slight nausea and it continued long enough to let the time for the passion to pass over’.

This article is a story, crafted and written with the perspective of the author who does wish to make a political point about the treatment of criminals. I probably picked out the scenes of dancing, music and gave close attention to the patient environment as this is something I do during my present role with ArtCare at Salisbury District Hospital. However, when you read the full article, see below, ask yourself, does it highlight to us, the reader, our own pre-conceptions and unconscious bias on the topic? Does it challenge our modern concepts of Victorian mental institutions? Are you convinced by the description of treatment? Is it a gentile façade hiding problems within Victorian society? Are we more open on the topic now? Have our attitudes changed, or not?

Read William Gilbert’s ‘A visit to a Convict Lunatic Asylum’ full article

Further reading

- Read more about the history of the Old Manor Hospital

- Find out about the tunnels under the Old Manor Hospital

- The Old Manor Hospital League of Friends leaflet makes an interesting read

- We also have an Old Manor Nurse Recruitment brochure in our collection dating back to the 1970s, containing images of the facilities available at the site. A fascinating glimpse into the past

- Take a look at the Old Manor Hospital guide for patients and relatives circa. 1980s