Feeding Body and Soul

Provisions and victualing at the Infirmary (1766–1858)

In the early days of hospital care, food wasn’t just nourishment, it was part of the treatment. At the Salisbury Infirmary, diet played a critical role in patient recovery, with records from as early as 1766 noting that “the simplicity and regularity of diet, with which the poor are kept in a hospital, contribute much sooner to their recovery, than their own way of living.” However, there was also a recognition that many discharged patients wouldn’t be able to afford such structured diets once they returned home.

By 1767, food procurement became more formal. The Committee advertised for sealed bids to supply provisions, stating that “the most reasonable proposals will be accepted”. This was a move aimed at fairness, though later events suggest favouritism wasn’t unheard of.

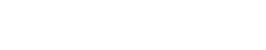

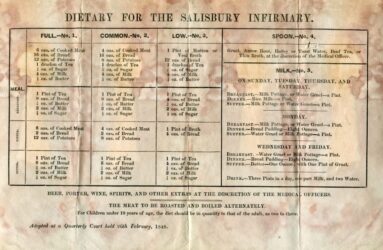

By 1768, the Infirmary had implemented a highly detailed dietary system. Patients were assigned to one of four specific diets: Common, Low, Milk, or Dry each had clear weekly menus. For example, on Wednesdays, a patient on the Common Diet received:

- Breakfast: a pint of milk pottage

- Dinner: 8 ounces of boiled mutton

- Supper: a pint of broth

Meanwhile, a patient on the Dry Diet had:

- Breakfast: 2 ounces of cheese

- Dinner: baked bread pudding

- Supper: another 2 ounces of cheese

Meat allocations were strictly monitored: Common Diet patients received 4 pounds of meat per week, Low Diet patients got 2 pounds and those on Milk Diets received no meat at all. Bread and beer were portioned too. Everyone got a 15-ounce loaf per day; but beer was limited to a pint per day for Low Diet patients and half a pint for those on Dry Diets. Milk Diet patients drank a mix of milk and water, totalling three pints daily.

Interestingly, the 1768 budget also included sugar and fruit, recognizing the role of varied nutrition in healing.

Not all dietary policies were embraced without resistance. In 1776, the Committee took a strong stance against patients drinking tea excessively:

“if such irregularities be continued, contrary to the orders of the Physicians and Surgeons, the offenders should be discharged.”

In 1804 it was ordered that “… one pint of beer be allowed each patient daily, except on low diet, three pints to each Nurse, and two pints to the other servants … the House Surgeon advised that there were no patients in the Institution on beer, only two on stout”.

Yet by 1810, tea was still considered essential for some: green tea was ordered for the Matron and Apothecary, while cheaper Bohea tea (blend of Chinese black teas) was provided for the nurses.

The quality of consumables also came under scrutiny. In 1858, the House Surgeon reported that poor-quality beer, brewed in-house by the porter (who also baked and gardened), was making patients ill. The Committee agreed this was unsustainable and switched to beer from Higgins Brewery (Bedford) at 1 shilling per gallon, ending the in-house brewing practice.

Meanwhile, spirits consumption dropped sharply from 36 gallons in 1857 to just 16 gallons in 1858 without explanation, perhaps reflecting shifting attitudes toward alcohol in medical care.

From structured menus and meat rations to tea controversies and budget battles, the history of provisions at the Infirmary offers a rich picture of healthcare in the 18th and 19th centuries. These records show that healing the body was as much about everyday sustenance as it was about medicine and that managing food, drink and supplies required as much care as administering a cure.

Written from research by Stuart Wakefield, The Salisbury Infirmary 1767-1870