A cheap holiday and a curious experiment

Caroline first volunteered at the Common Cold Unit between 1976 and 1981, returning a total of six times. At the time, she was a student nurse and later a qualified staff nurse. Like many volunteers, she was initially drawn in by a simple and practical reason. “Basically, it was a cheap holiday,” she said. An advert in a nursing journal promised ten days of accommodation, meals, travel paid, and a pound a day pocket money. “Everybody thought I was absolutely crackers,” she recalled, “but I loved it.”

Her first visit was something of a leap into the unknown:

“I didn’t know what was going on at all,” she said. Volunteers were dropped off at the office, given their keys, and then largely left to settle in. The office staff, particularly Audrey, were remembered fondly for their warmth and efficiency. “They were very good at matching people up,”

Caroline said. Sometimes she shared a flat with others; on one occasion she stayed alone, which she enjoyed. “I used to take my sewing machine with me,” she explained. “I was quite happy on my own.”

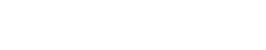

Accommodation was in converted huts linked by wooden walkways, exposed to the wind and weather. Inside, everything felt outdated but comfortable. “It was all very old-fashioned,” Caroline remembered, “but that was part of the charm.” Meals were delivered twice a day in large vacuum flasks and left in boxes outside the huts. Once a trial began, contact with other volunteers was restricted to prevent cross-infection. “You certainly couldn’t speak to people face to face,” she said. “There was a thirty-yard limit, so you were sort of bellowing at people across the field.”

Despite the restrictions, Caroline found the experience deeply relaxing. She usually volunteered in October, enjoying the countryside around the Unit. “It was just a beautiful area,” she said. “We’d sit out in the sun, read books, go for walks.” Volunteers were encouraged to explore as long as they avoided close contact with others. Mrs Andrews, the matron, was a memorable presence. Locals were used to seeing volunteers, and if contact was unavoidable, Mrs Andrews advised them to “put a tissue over your face and walk snootily by.”

The medical routines were straightforward but occasionally uncomfortable. Volunteers took their temperatures daily, handed in used tissues to be weighed, and underwent nasal washings by laboratory staff. Caroline only became unwell once, describing it as “a mild bout of Russian flu.” One year she took part in a drug trial that required extensive urine sampling. “They wanted hourly blood tests,” she recalled, “but they said the volunteers would never consent, so we had to do twenty-five urine collections instead.”

Caroline met many people during her stays, nurses, medical students, housewives, unemployed people, and others from all walks of life. “It surprised me how varied it was,” she said. Although she didn’t keep in touch with anyone afterward, she valued the mix of people and the freedom to return year after year when her nursing shifts allowed. “I just got into a habit,” she explained. “I liked coming.”

Years later, when Caroline found photographs, badges, and a 1979 Nursing Times article featuring her while moving house, the memories came flooding back. She reflected on the Common Cold Unit as a place that was “quaintly old-fashioned” but exceptionally kind. “They really looked after you,” she said. For Caroline, the Unit was far more than a research facility, it was a retreat, a formative experience, and a small but meaningful chapter in a long and adventurous nursing career.